How animals behave…

Oxpeckers not only remove ticks, but also act as an early-warning system for approaching danger.

Ethology, simply put, is the science of animal behaviour. It is an intensely fascinating subject- one which enhances your viewing pleasure in any wildlife area. The interactions between animals are fascinating, and the more you understand, the more meaningful your time will be. Peter Apps in his highly recommended book “Wild Ways” (a worthy purchase if you spend time in the bush), describes behaviour as “what an animal does, from a mouse nibbling a seed to a lion pride pulling down a buffalo bull, from a dominant male baboon’s stern glance at a subordinate to the dramatic clash between fighting elephant bulls in musth”. The science studies all the facts, and then tries to extrapolate the “why” to learn more about each animal. A commonly quoted term amongst field guides is “The animals don’t read the text books”, and so for every generalisation you have exceptions. But that’s what makes the world interesting ????.

According to Apps, one can view an animal’s behaviour and try interpret it against four questions. Bear in mind throughout that an animal doesn’t “waste hard-earned energy” – there are generally good reasons for a behaviour, ultimately leading back to one goal: survival and thus procreation. The first question is “what caused the animal’s behaviour”? Or put another way, what stimulus from the environment or change within the animal led to the action? Secondly, is it a learned behaviour or was the animal born with it i.e. instinct? Thirdly, what is the purpose of the behaviour? What does it provide or what are the benefits in terms of contributing to survival and/or breeding success? The final question relates to evolution: what ancestral behaviours gave rise to the current situation, and how did they evolve to be in their present form?

Almost human…

Let’s take a look at some interesting examples. In a vervet monkey troop, the young vervets inherit their mother’s rank. A mother, her offspring, their babies and even relatives that are more distant will support each other in a dispute. The dominant males are sought-after as mates (best genes), and the dominant females are able to get better access to resources. Interestingly, if a lower ranking individual is threatened or bitten by a dominant individual, there is no retaliation. That said, they rather tend to attack a monkey lower down the hierarchy. Vervets have many different calls (at least 36), and their alarm calls are predator specific (allowing them to take the appropriate evasive action thus prolonging survival). It takes youngsters approximately four years to learn all the calls. These clever creatures also respond to the alarm calls of birds. Vervets rub their chests and cheeks onto the branches of trees to scent-mark their home territory. Friendly relations within a troop are maintained with the use of allogrooming (social grooming which serves to signal and/or reinforce social bonds). The babies in a troop are cared for by all the females, and the entire troop will rush to the rescue of a youngster in trouble. So very social animals with complicated interactions.

Tails in the air like little aerials… There’s a reason for that.

When on a game drive, one almost always comes across warthogs. They too deserve attention and are in and of themselves very interesting. Mainly active during the day (diurnal), at night they retire to a burrow (often an aardvark burrow adapted to their liking) for both protection and warmth. The females use grass to line their burrows – as insulation against the cold. As a rule, they reverse in, so their tusks face any incoming intruders. This works for most predators except lion, who have been known to dig them out. Warthogs live in little groups (sounders), usually consisting of one or two sows and their piglets. When disturbed, the mother runs off and the piglets follow – all with their tails in the air in order to keep track of one another in the long grass.

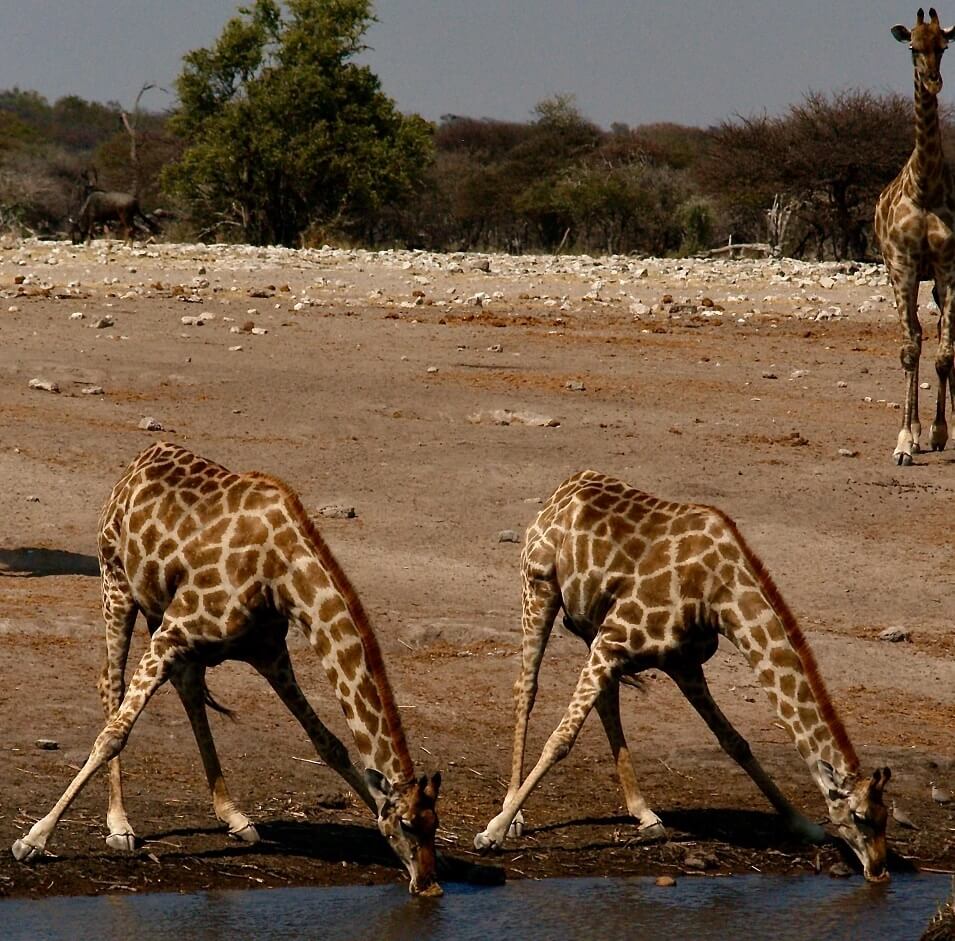

Drinking should give giraffe a huge head rush, but they have a clever system of valves that regulate the flow of blood to the brain. As a rule, one always “stands guard” whilst the others drink.

Often, if you ask a game ranger what the most common request on an overseas visitor’s wish list, a giraffe is right up there. As a rule, these tall animals feed during the cool parts of the day, resting during the night and the heat of the day (either whilst standing or lying down). When it sleeps, it is only for very brief periods of time with its head pillowed on its body (it has one of the shortest sleep requirements of any mammal). They sleep for a maximum of half an hour per day, five minutes at a time! Which is why you are very lucky if you happen to “catch” them in this position (which is also part of the reason they do this – to limit the risk of being caught unawares by lion).

Two rams squaring up for a territorial fight.

So very often one hears the comment “Oh, it’s just impala again!”. They have a number of interesting behaviours worth watching out for. When startled by a predator, the herd will explode in all directions. They have been known to leap up to three meters high and to cover ten meters in a single bound. This chaos makes it difficult for the predator to lock onto a single target. The black tuft of hair on an impala’s hindleg surrounds a gland, which produces a secretion with “a pleasant cheesy smell”. No one is yet entirely sure of the function of this, but one theory is that the gland is opened during the chaos to leave “an airborne scent trail” for the herd to follow. Rutting males are the least alert of all – they have other things on their minds! Usually, males of between three and a half and eight and a half years old hold territories and are in their prime. But between all the roaring, and chasing, and fighting, and mating, and herding females, and scent-marking territory (by rubbing glandular skin of forehead and face on vegetation), that peak condition doesn’t last very long as they don’t have much time to eat! In peak breeding season, a territorial ram’s tenure is seldom more than eight days.

The black tuft of hair on its hindleg surrounding the gland is very clearly visible here.

One can go on forever, which is why I find this such a fascinating subject. A highly complex and often amusing exercise is to consider the human being in terms of Ethology. But I digress… We hope you have enjoyed this small insight into the world of animal behaviour and highly recommend that you investigate further if it is something that interests you!

Have a great weekend,

Jacqui Ikin & The Cross Country Team

INFO BOX

Warthog Family Preparing their Burrow for the Cold Winter Night:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6v6VL_QemVI&t=78s

Giraffe Sleeping:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTd9zKFWHLY