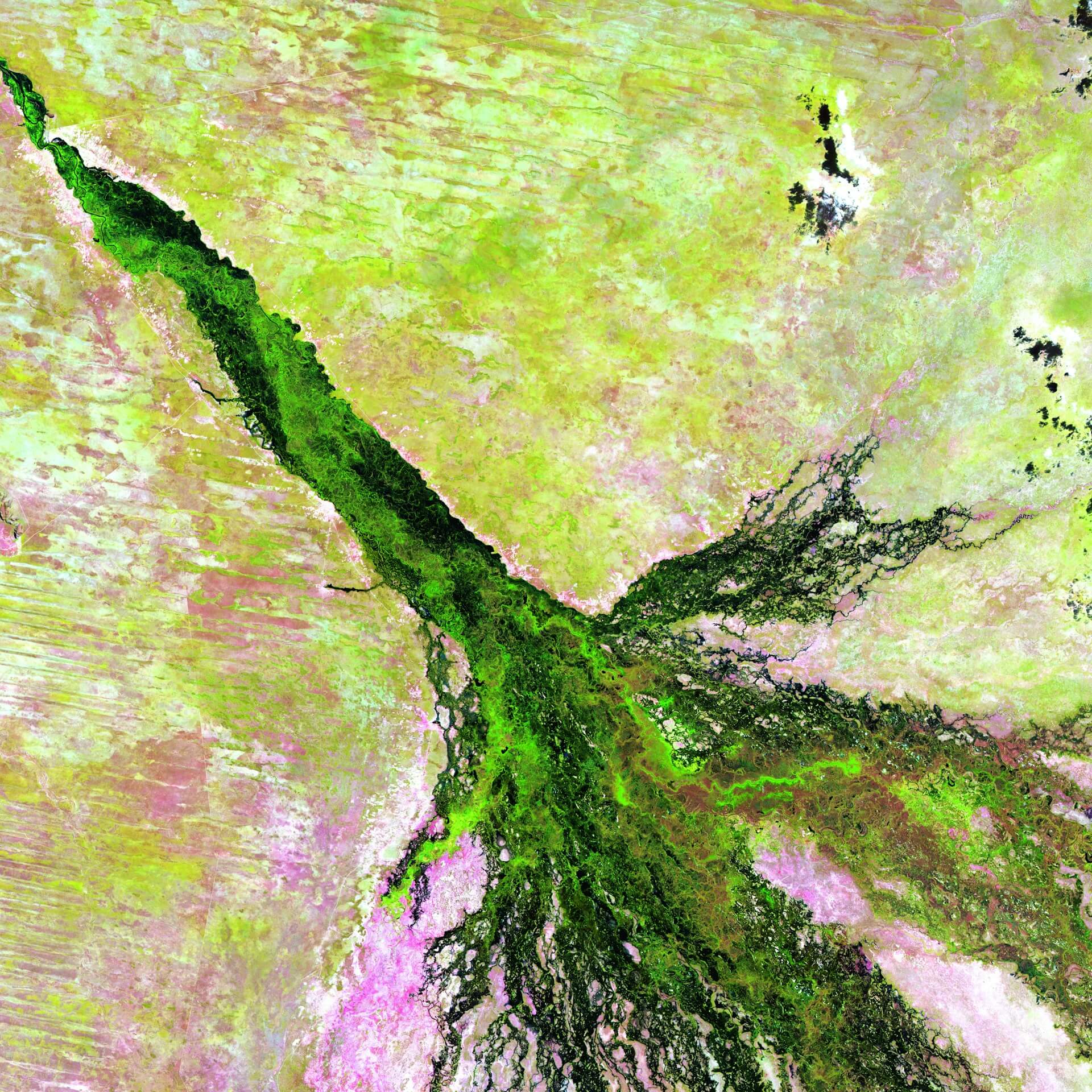

The Okavango Delta

Nature is beyond incredible – purely on a level of “how amazing is this organism”. Occasionally though, you get a system that is just so unusual, so finely tuned, so well balanced, that it takes your breath away… The Okavango Delta is one such system.

In most cases, rivers flow into the sea… An “endorheic basin” is defined as ‘a region in which the river network is completely isolated from the ocean’ – i.e. it has no outlet. The Okavango Delta (going forward we’ll simply refer to it as the ‘Delta’) is a perfect example of this feature, and the Okavango River simply ends in the Kalahari Desert.

It is also a fairly obvious statement that rivers flow ‘downhill’. The story of the Delta originates from the interior Bié Plateau of the Angola Highlands. Angola is considered a ‘water tower’, and the water flows into the Okavango River from two tributaries from this area – the Cuito and Cubango Rivers. There is less than two metres variation in height across the entire 250-kilometre length of the Delta – which explains why the water fans out in the way it does. This really is a completely unique system, as the water results in a maze of winding channels, oxbow lakes, islands and floodplains.

The summer rainfalls that take place in the Angolan highlands in January and February eventually drain into the Delta – all eleven cubic KILOMETERS of water (note that in this article, we are using figures from ‘normal’ years – not 2024 which finds the whole region in the grip of an awful drought). A surge of around 1200 kilometres in a month occurs in Botswana between March and June. It is during this time that the Delta is at its largest. These waters spread over an area of between 6,000 and 16,000 km2. As always, numbers vary according to source, but it is still considered the largest inland delta in the world. In fact, it is so large that, at its fullest. it is large enough to be seen from space!

The Okavango River enters Botswana from Namibia as a single meandering channel, following a minor north-west to south-east rift that forms the ‘Panhandle’ of the Delta. One fault (Gumare), running north-east to south-west, limits the northern end of the wetland, and two parallel faults (Kunyere and Thamalakane) the southern end. When flows are high, the water from the Delta reaches the Thamalakane river, which flows through Maun and then into the Boteti River, and the Nhabe and Kunyere Rivers, which flow south-west into Lake Ngami. It is a great tradition to watch for and monitor when the waters will reach Maun’s Thamalakane River.

The rainy season in the Delta is November/December through to March/April – which is then followed by the flooding from Angola somewhere between March and June. What is interesting is that the annual flooding from the Okavango River occurs during the dry season, with the interesting result that the indigenous plants and animals have synchronized their biological cycles with these seasonal rains and floods.

The islands of the Delta mostly start as termite mounds (70%) and often have white patches in their centre where the high salt content of the islands collects. This process causes the islands to become toxic and trees die off in the centre.

Another point that makes the Okavango unique is the fact that it is a freshwater alluvial fan. Most interior drainage systems (rivers that do not reach the sea) are saline because the only outlet for the water is via evaporation which leaves salts, which is what occurs on the Makgadikgadi Pan. However, the Okavango Delta has outlets (mentioned above). Although only about three percent (numbers changes year on year) of the Okavango’s inflow actually flows out via these outlets, this is enough to keep the Delta fresh water rather than saline.

The mokoro is a traditional canoe/dugout used to travel through these wetlands. The term “mokoro” specifically refers to the boats used by the local people known as the Bayei and the BaYei people. As the environment is better protected, modern mokoros are often made from fiberglass.

They are long and narrow, with a shallow draft, which allows for navigating the waterways through shallow waters, reeds, and lily pads. These craft are traditionally propelled by standing at the rear of the boat and using a pole to push against the riverbed. The boatmen, better known as “polers”, are exceptionally skilled and this is one of the most peaceful ways of experiencing the Delta.

The ecological importance and ‘Outstanding Universal Value’ of the Okavango Delta has been recognised by UNESCO and the RAMSAR Convention. The Okavango Delta was designated a Wetland of International Importance in 1996 and a World Heritage Site in 2016.

It has many other accolades, but for me, it is simply one of my favourite places in the entire world. It is also relatively easy to access, and truly a “must” for anyone who loves Africa.

Jacqui Ikin & The Cross Country Team